From Flash Boys to Formalized Blockspace: The Evolution of MEV in Crypto

What is MEV? Definition and TradFi Parallels

Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) refers to the maximum profit a blockchain block producer (whether a miner, validator, or sequencer) can extract by arbitrarily including, excluding, or reordering transactions in the blocks they produce (flashbots). In essence, MEV captures the value available to privileged actors who control transaction ordering beyond the standard block rewards and fees. This concept was originally coined “Miner Extractable Value” in the context of Ethereum’s Proof-of-Work era, but it has since been generalized to “Maximal” as it applies to any block producer in Proof-of-Stake and beyond (whitestork).

MEV has clear parallels to practices in traditional finance. It resembles the dynamics of high-frequency trading (HFT) and front-running on Wall Street, where firms exploit tiny time advantages and ordering priority for profit (whitestork). For example, just as HFT firms co-locate servers to trade milliseconds faster than others, blockchain “searchers” (bots hunting MEV opportunities) engage in latency wars – sending transactions faster or in greater volume to beat competitors. In regulated markets, certain HFT strategies (like market arbitrage) are legal and even improve efficiency, whereas blatant front-running customer orders is illegal. In decentralized finance (DeFi), however, the playing field is an open mempool where any actor can attempt to profit from seeing others’ pending transactions – effectively institutionalizing a form of latency arbitrage and front-running that traditional markets ban. This “Flash Boys” phenomenon in crypto (alluding to Michael Lewis’s book on HFT) was first flagged by researchers around 2014 and highlighted in the 2019 Flash Boys 2.0 paper, which brought awareness to how public mempools enable exploitive strategies. Since then, MEV has been recognized as a critical issue not just on Ethereum but across many blockchain ecosystems.

Forms of MEV: Parallels to Traditional Market Strategies

Key forms of MEV mirror both beneficial and harmful trading strategies known in finance. Notable categories include: DEX arbitrage – where bots capitalize on price differences for the same asset across exchanges (e.g. buy low on one DEX, sell high on another) (bloghack); sandwich attacks – a form of predatory front-running and back-running around a victim’s trade (inserting a buy just before a large trade to push the price up, then a sell right after, siphoning value) (whitestork); and liquidations – where bots monitor lending platforms and swiftly repay defaulted loans to claim collateral, a necessary function for market health that also yields profit (helius). Other examples include back-running (e.g. sniping NFT mints or reacting to oracle updates)(whitestork) and even “time-bandit” attacks (reordering past blocks) (whitestork). In traditional finance, activities analogous to sandwich attacks would violate market rules, whereas arbitrage and liquidation-like strategies (e.g. real-time arbitrage or margin call liquidations) are legitimate. This comparison highlights how MEV is essentially the crypto analogue of Wall Street’s race for alpha – but playing out on-chain in a transparent, permissionless arena. The result, if unmanaged, can be “toxic” MEV that harms users (eg. higher slippage and fees due to front-running) and network instability (congestion from bot spamming), much as unregulated front-running would undermine fair markets (flashbots). These concerns have driven the crypto community to seek solutions that both mitigate the negatives of MEV and formalize its extraction into fairer, more transparent mechanisms.

The table below provides a concise overview of these common MEV extraction strategies, detailing their mechanisms and impacts.

Table 1: Common MEV Extraction Strategies

| Strategy | Description | Impact on Users | Impact on Network |

|---|

| Arbitrage | Exploiting price discrepancies for the same asset across different Decentralized Exchanges (DEXs) by buying low and selling high. | Generally low impact; can lead to better prices over time as markets align. | Helps align prices across DEXs, contributing to market efficiency. |

| Sandwiching | Placing a buy order immediately before a user’s transaction and a sell order immediately afterward, profiting from the user’s slippage. | Higher transaction costs due to increased slippage and worse execution prices. | Can lead to network congestion from competitive bidding (PGAs) and wasted block space. |

| Liquidations | Triggering the liquidation of under-collateralized loans in DeFi lending protocols to earn a fee. | Loss of collateral for the liquidated user. | Essential for protocol solvency and stability of lending markets. |

The MEV Terrain From Ethereum to Solana and Layer 2s

As MEV became evident on Ethereum and beyond, each blockchain ecosystem developed its own approaches to manage and harness it. Below we survey the current MEV space and the various mechanisms put in place to manage and prevent them.

Ethereum (Mainnet – Proposer/Builder Separation and Flashbots): Ethereum’s public mempool and DeFi richness made it ground zero for MEV. Early on, arbitrage bots would engage in priority gas auctions (PGAs) – bidding up fees to get priority – which led to network spam and miners privately extracting MEV. In response, the Flashbots research collective emerged in 2020 to “democratize” MEV extraction (flashbots). Flashbots introduced an off-chain auction where searchers submit transaction bundles directly to miners (now validators), along with bids (tips), in a sealed-bid format (flashbots). This system allowed MEV to be extracted cooperatively without clogging the public mempool, and it spread rapidly – by mid-2021 over 80% of Ethereum’s mining hashrate ran Flashbots’ MEV-geth client to accept these bundles (flashbots). After Ethereum’s switch to Proof-of-Stake, Flashbots’ MEV-Boost software enabled an interim form of Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS): validators outsource block construction to a competitive marketplace of builders in exchange for MEV-derived fees (flashbots). This boosts validator rewards and neutralizes the advantage of running private MEV strategies, thereby helping decentralization of staking by letting even solo validators capture MEV (flashbots). However, it also introduced new centralization risks – over time a few builders and relays gained a large share of blocks, raising concerns about censorship and single points of failure. To address this, Ethereum’s community is actively researching in-protocol PBS and novel architectures. One notable vision by Flashbots is SUAVE (Single Unifying Auction for Value Expression) – a decentralized, MEV-aware block building network. Announced in late 2022, SUAVE is described as “the start of a new cooperative phase of MEV” aiming to decentralize the block-builder role and combat the centralizing forces of exclusive order flow. It proposes a privacy-preserving, encrypted mempool and cross-domain block auction that could unify MEV markets across Ethereum and other domains, ensuring maximal revenue for validators and better execution for users without relying on any single trusted relay (flashbots).

Solana (High-Throughput Chain – Jito and the Rise of BAM):

Solana’s high TPS and unique architecture (e.g. no global mempool by default, leaders scheduled in advance) gave it a different MEV profile. In Solana’s early days, the absence of a traditional mempool and its rapid block times limited obvious front-running; however, MEV still manifested in forms like DEX arbitrage, liquidations, and NFT mint sniping (helius). Searchers began to spam validators with massive numbers of transactions to win arbitrages, exploiting Solana’s ultra-low fees (squads). This caused network strain and contributed to outages in 2021–22 during peak NFT drops and arbitrage storms. To curb this and capture the value more efficiently, Solana turned to Jito Labs, a core infrastructure team focused on MEV. Jito introduced an out-of-protocol MEV auction system for Solana, centered on a modified validator client (Jito-Solana) that many validators voluntarily adopted. By 2024, over 65% of Solana validators were running Jito’s client to access these MEV optimizations (helius). Jito’s infrastructure included several innovations: (1) Bundles – searchers could submit lists of transactions that execute atomically (all-or-nothing) to ensure complex arbitrages or liquidations occur as intended (squads); (2) a Block Engine – an off-chain service that simulates and evaluates many bundle combinations, then forwards the highest-paying one to the leader validator for inclusion (squads); and (3) a Relayer – a network layer to privately propagate bundles and standard transactions to validators, reducing spam and enabling fair access (squads). Instead of a public mempool, Solana under Jito operated a “pseudo-mempool” where transactions waited briefly (e.g. 200ms) for bundles to form and bids to be made. The winning bundle (with the highest tip to the validator) would then be included in the next block, while others were dropped – vastly cutting down on spam and failed arbitrage attempts (helius). This system yielded significant revenue: by early 2024, Solana validators were earning millions of dollars in tips from Jito-facilitated MEV auctions (helius). Importantly, Jito aligned incentives with the broader community by launching a Jito-SOL stake pool – a liquid staking token that directs delegated SOL to Jito-running validators and shares MEV profits with those stakers (squads). In other words, users who stake with Jito’s pool indirectly receive MEV rewards on top of normal staking yield, distributing value that would otherwise be kept by searchers or validators alone (squads).

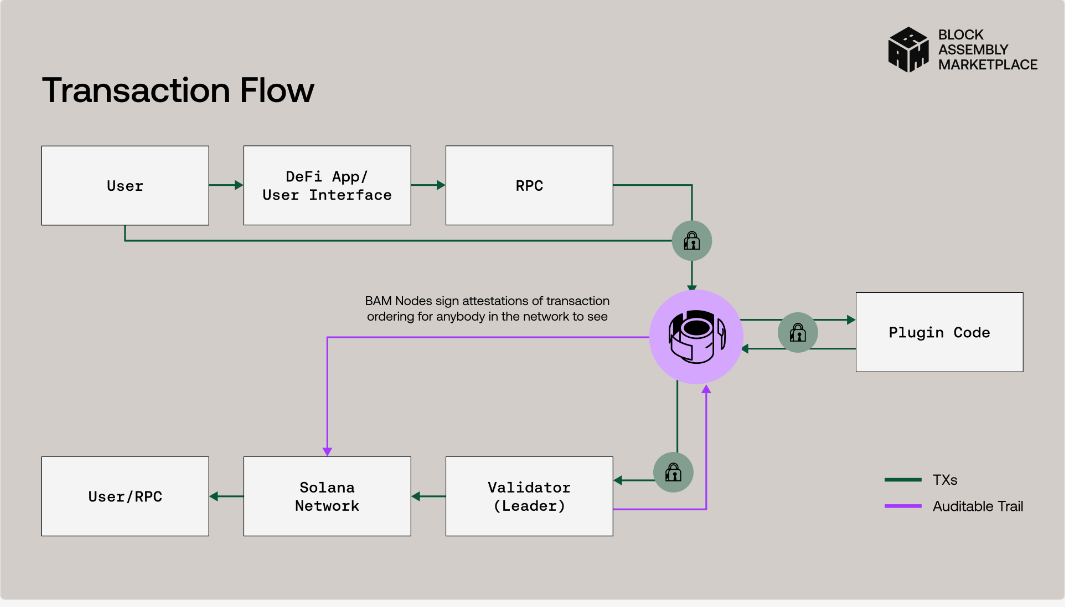

Jito’s latest initiative: BAM (Block Assembly Marketplace). Launched in mid-2025, BAM represents a next-generation block-building architecture for Solana, moving the chain into a new era of structured MEV management (coindesk). BAM introduces a formal marketplace for transaction sequencing, built on Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) for privacy and fairness. Concretely, BAM is composed of three core components (coindesk): BAM Nodes – a network of TEE-enabled scheduler nodes that privately receive and order transactions inside secure enclaves, producing an encrypted, verifiable ordering (think of them as specialized block builder servers) ; BAM Validators – Solana validators running the updated Jito client that trust the BAM Nodes’ ordered output and execute transactions accordingly (newswire); and Plugins – a novel concept of programmable interfaces that let developers and traders inject custom logic into the scheduling process (newswire). Through Plugins, anyone can write modules to achieve specific transaction ordering policies (for example, a decentralized exchange might create a plugin to enforce batch auctions or fair sequencing for its trades) – effectively enabling “application-controlled blockspace” as a new primitive. Fees generated by these plugins (users/developers might pay for guaranteed ordering or inclusion logic) become a new revenue source that is shared across the ecosystem: plugin creators earn a portion, while BAM node operators, validators, and even SOL stakers share the rest via built-in revenue-sharing. The upshot is a more transparent and collaborative MEV supply chain: transaction order is determined by explicit algorithms and bids rather than ad hoc spam, and the value extracted is distributed to those securing and building on Solana, not just to opportunistic bots. BAM’s design prioritizes verifiable fairness and privacy – transactions remain encrypted in the TEEs until execution, preventing mempool-based frontrunning, and each ordered batch comes with a cryptographic attestation that validators followed the prescribed ordering. This creates an audit trail visible to everyone, holding block producers accountable. According to Jito, these features will enable “faster, fairer trading” for users and “auditable markets with execution assurances that rival TradFi” for institutions (newswire). Developers, too, gain a new sandbox to build advanced market mechanisms (like on-chain order books, matching engines, dark pools, etc.) that were difficult on a first-come-first-serve chain(thedefiant). In short, Solana is evolving MEV from a Wild West of spam into a formal blockspace economy – one that is programmable and user-aligned. BAM is launching in phases with a small set of top validators (e.g. Figment, Helius, Triton One) participating initially (coindesk). The plan is to gradually decentralize the BAM node operator set, open-source all code, and eventually allow anyone to run a scheduler node or write a plugin, under community governance (newswire). This mirrors Ethereum’s PBS vision but tailored to Solana’s high-performance context – highlighting that despite technical differences, both ecosystems are converging on the idea of MEV as a managed market rather than a free-for-all.

Jito Labs and Solana’s Block Allocation Market (BAM)

To understand the significance of Solana’s Block Assembly Marketplace (BAM), it’s important to recognize the role Jito Labs has played in Solana’s validator infrastructure and MEV journey. Jito Labs emerged as the premier MEV and infrastructure provider in the Solana ecosystem, analogous to Flashbots on Ethereum. Their mission from the outset was to “minimize negative externalities while enabling validators and stakers to maximize their share of MEV” (jito-foundation). In practice, Jito built the custom validator client (Jito-Solana) and off-chain auction network described earlier, which not only mitigated spam but also significantly boosted validator earnings on Solana (squads). By introducing bundled transactions, a block engine, and a fast relayer network, Jito allowed Solana’s high-throughput chain to handle MEV extraction in a controlled way (squads). One of Jito’s notable innovations was the JitoStake pool (JitoSOL) – a decentralized staking pool that pays delegators yield from MEV profits. This meant even regular SOL holders could indirectly benefit from MEV rewards gathered by top validators, aligning the broader community’s interests with MEV rather than pitting users entirely against searchers (squads). Jito Labs also worked closely with the Solana community on policy; for example, in 2023 many Solana validators (including Jito) collectively agreed to disable Jito’s own “mempool” feature that enabled sandwich trading, thereby sacrificing some short-term MEV income in favor of user fairness and long-term network health (helius). This ethos of balancing profit with ecosystem growth set the stage for BAM.

Block Allocation Market (BAM) is essentially Jito’s next-generation solution – taking the lessons of the past two years to formalize MEV extraction as a first-class part of Solana’s architecture. Announced in July 2025 with support from the Jito Foundation, BAM is described as “a fundamental shift to how Solana transactions can be sequenced and how blocks can be built” (thedefiant). At its core, BAM decouples the transaction scheduling from the core consensus, introducing a new layer of specialized nodes and markets. The three pillars of BAM – BAM Nodes, BAM Validators, and Plugins – have been discussed, but let’s break down their importance:

- BAM Nodes (Scheduler nodes with TEEs): These are perhaps the most critical piece. By using Trusted Execution Environments, the BAM Nodes can accept transactions and bundle/order them while keeping the contents encrypted (devbam). This means no one (not even the node operator) can see the transactions before they’re finalized, preventing any preemptive exploitation. The BAM Node produces a cryptographically signed ordering of transactions and sends this to the Solana leader (the validator assigned to produce the next block) (bamdev). Because of the TEE, the network can trust that this ordering wasn’t tampered with or leaked (attestations prove the node was running the approved code) (bamdev). In effect, BAM Nodes act as block builders that the validators agree to follow – injecting an element of verifiable randomness/privacy into Solana’s block construction. This greatly mitigates “seeing into the mempool” style MEV (which was already limited on Solana) and levels the playing field for searchers. Rather than needing a privileged partnership with a validator, anyone can submit to a BAM Node and know their strategy stays private until execution (newswire).

- BAM Validators (Jito-enhanced validators): Validators running the BAM-enabled client will yield some control to the BAM Nodes’ instructions – they will include the transactions in the exact order provided, as long as the attestation checks out (newswire). This is a significant change in the validator’s role: traditionally, Solana leaders had sole discretion of ordering; under BAM, they become executors of an order determined by the scheduling layer. It’s a voluntary choice – presumably validators opt in because it increases their revenue (they get a share of MEV or plugin fees) and provides better service (fair ordering) to users. Initially, a set of reputable Solana validators (Figment, Helius, Triton One, and others) are collaborating with Jito in the alpha rollout (newswire). The goal is to rapidly scale up participation such that eventually a large portion of stake (30%+ in a later phase) uses BAM, after which it could become a new standard (bamdev). Importantly, the design is opt-in and off-chain, meaning it does not require a hard fork or change to Solana’s consensus – it’s an overlay network that augments how blocks are assembled. This allows experimentation and gradual adoption without risking the base protocol.

- Plugins (Programmable transaction logic): Perhaps the most novel element, Plugins turn the blockspace into an open market for innovation. A plugin is like a custom rule or algorithm that a developer can deploy to a BAM Node, influencing how it orders transactions (newswire). For example, a decentralized exchange could deploy a plugin that batches all trades in a given timeframe and matches them using a uniform clearing price (preventing sandwiches and improving price fairness). Or an oracle provider could ensure its price update transaction is always placed at the top of a block and cannot be frontrun. Because the BAM Node operates privately and can enforce these rules, such plugins can guarantee execution properties that previously relied on trust or off-chain coordination. Plugins essentially allow specific MEV strategies or anti-MEV protections to be codified at the block-building level. They are also monetized: if your plugin provides value (say it improves user trade execution or captures arbitrage for an app’s treasury), you can charge a fee for transactions that use it (newswire). Those fees are then split: part to the plugin developer, part to the BAM operator/validators/stakers who secure the execution (newswire). This creates a micro-economy of MEV where, for instance, an app can earn from the MEV generated by activity within it (a concept similar to “application-specific MEV capture”). It’s a big shift from the world where all MEV is extracted by external bots – instead, MEV becomes cooperative and value-accretive. Jito’s team explicitly noted this opens a design space for things like on-chain order books, matching engines, and even dark pools that were hard to do on Solana before (thedefiant).

The implications of BAM for Solana’s MEV supply chain are far-reaching. For one, it greatly improves transparency: every block built via BAM comes with public attestations of ordering, so any deviation or malicious behavior by a validator (like not following the agreed order) can be proven and slashed or penalized (bam.dev). It also protects users by keeping transactions confidential until execution, meaning strategies like sandwich attacks are largely eliminated (a malicious BAM Node could not leak or reorder individual user txs without breaking its TEE, which would be evident). At the same time, it unlocks new value: previously, if a DeFi app on Solana wanted to prevent MEV, it had to design clever in-protocol mechanisms; now it can potentially rely on BAM’s infrastructure (e.g. writing a plugin) to handle it. If it wanted to capture MEV (say to fund its DAO), it could do so via plugins as well. In essence, BAM “markets” out Solana’s blockspace – turning what was once an opaque competition into an organized marketplace. This is why the initiative is called Block Assembly Marketplace: blocks aren’t just produced, they are composed via a market process.

From an incentive standpoint, Jito is also ensuring the value flows to the community. They recently proposed that 100% of fees collected from BAM and the existing Jito block engine go to the Jito DAO treasury, as opposed to a split where the core team kept a share (thedefiant). This means all MEV revenue (e.g. plugin fees, auction fees) would ultimately be controlled by Jito’s token-holding community, funding grants or buybacks as decided by governance (thedefiant). This move, along with plans for open-sourcing and permissionless participation, aims to dispel concerns that introducing a sophisticated block building layer could centralize power. Jito’s approach thus far has been to bootstrap the system (they’ll run the initial scheduler nodes and coordinate early validators) but then gradually hand it over to the decentralized Solana community (devbam). In summary, with BAM, Solana is at the cutting edge of formal MEV infrastructure: it’s integrating ideas similar to Ethereum’s PBS and encrypted mempools, but also pushing further with programmability (plugins) and hardware-enforced fairness (TEEs). As BAM rolls out, all eyes will be on metrics like: reduction in failed/arbitrage spam transactions, increased validator rewards and stake APR, and whether new financial primitives (like on-chain order books) bloom on Solana thanks to this reliable execution layer.

Arbitrum’s Timeboost: Time+Tip Auction for L2 Sequencing

On Ethereum’s Layer 2 networks, MEV takes on new twists due to the presence of a central sequencer in most rollups. The sequencer orders user transactions before batching them to L1, which creates an MEV opportunity at the L2 level. By default, leading rollups like Arbitrum and Optimism have used a simple First-Come First-Served (FCFS) ordering policy – the sequencer takes transactions in the order they arrive, which is easy to reason about and, with a private sequencer mempool, protects users from being frontrun or sandwiched (medium) (arbitrumforum). However, FCFS introduced a different kind of competition: latency wars among MEV searchers. For instance, on Arbitrum, arbitrage bots would spam the sequencer or try to co-locate infrastructure to ensure their transaction arrived microseconds before a competitor’s, winning the right to an arbitrage or liquidation (arbitrumdocs) (arbitrumforum). This led to wasted resources (lots of spam transactions in the sequencer’s inbox) and meant that 100% of MEV profits went to the fastest bots, with none returning to the chain’s community or token holders (docs.arbitrum) (arbitrumforum). In 2023–2024, teams began devising more structured approaches for L2 MEV. Offchain Labs (the team behind Arbitrum) proposed Timeboost – a new transaction ordering mechanism that effectively combines time priority with a fee auction. Under Timeboost, Arbitrum’s sequencer maintains an “express lane” alongside the normal queue (docs.arbitrum). In continuous intervals (e.g. every block or every minute), a sealed-bid second-price auction is run among participants (typically sophisticated searchers) to control this express lane (docs.arbitrum) (arbitrumforum). The highest bidder wins and gains the ability to have their transactions included with a 200 ms head-start over everyone else for the next interval. All other transactions experience a tiny artificial delay (e.g. 200ms) before being sequenced, ensuring the auction winner’s advantage. Crucially, this does not give the winner unchecked power to reorder or censor transactions – they cannot see the contents of the private mempool and can only ensure their own txs land first in time, not that they can manipulate others’ relative order (docs.arbitrum). In effect, the Timeboost auction replaces the random latency race with a transparent market: to capture an arbitrage on Arbitrum now, a bot must bid and pay for priority rather than just spam the fastest. The winner’s payment is then collected as revenue for the chain’s DAO or owner (for Arbitrum One, this would accrue to the Arbitrum DAO treasury if approved)(arbitrumforum). This approach aims to “provide chain owners a way to capture MEV… and reduce spam from FCFS arbitrage” while preserving the user experience of fast confirmations and protection from malice (docs.arbitrum). Notably, Timeboost explicitly only gives advantage in time, not knowledge – the mempool remains closed, so even the priority holder cannot frontrun other users’ pending trades. They also can’t guarantee being first in every single block, just that their transactions bypass the imposed delay – natural network latency and competition in subsequent blocks still apply. This means harmful MEV like sandwiching remains effectively impossible, while “good MEV” like arbitrage and backrunning (liquidations) can be pursued via the express lane(arbitrum.foundation).

The significance of Timeboost for MEV management lies in its balance between preserving user experience and capturing value. Users who don’t participate in MEV games should hardly notice any difference – at most, their transactions might take 0.2s longer to be included, which is usually negligible (blocks are still extremely fast, and a 200ms delay is akin to a blink) (docs.arbitrum). Crucially, because the mempool stays private and the express lane confers no ability to peek at others’ transactions, users remain protected from classic frontrunning and sandwich attacks (docs.arbitrum). This means Arbitrum can claim it has no worse MEV security for users than before – the negative externalities (like failed trades or unfair slippage) remain mitigated by design. On the other hand, the positive MEV (arbitrage that keeps prices in sync, liquidations that keep lending protocols solvent) continues to occur, but now the chain captures a share of that value. This turns MEV into something that can fund the ecosystem rather than purely enrich private bots. It also reduces the incentive to spam: if you know you can’t beat the auction winner by brute force, you’re less likely to overload the sequencer with useless transactions. It’s effectively similar in spirit to PBS/Flashbots, but at an L2 level: an auction for ordering rights instead of an auction for block construction. The difference is that Arbitrum’s express lane is more granular (happening every block or minute) and it explicitly preserves the first-come ordering for everyone else with just a tiny tweak. One can think of it this way: Under FCFS, fastest network wins; under Timeboost, highest payer wins (but only in narrow slices), and the payment goes to the public good.

Other rollups are exploring similar or alternative MEV mitigations. Optimism, for example, has thus far stuck with an EIP-1559 style Priority Gas Auction (PGA) – meaning users/searchers bid a higher gas tip to get priority, much like Ethereum L1. This is simple but leaves MEV in the hands of fastest bots and doesn’t return value to the ecosystem (arbitrumforum). Projects like Polygon (which runs a quasi-independent chain) have trialed third-party solutions such as bloXroute’s FastLane, which share a portion of MEV profits with validators as a reward for including bundles, somewhat akin to Flashbots on Ethereum (arbitrumforum). In the Cosmos ecosystem, Skip Protocol offers opt-in MEV auctions for validators on various app-chains, again splitting revenue with the block producer (Medium). And in a more specialized vein, the API3 project introduced an OEV (Order Execution Value) Network aimed at oracle services – essentially letting data providers capture MEV that arises from the timing of oracle updates, rather than leaving it to arbitrage bots. Across these varied approaches, the common trend is clear: blockchains are moving from ignoring or ad-hoc battling of MEV, to actively structuring and channeling it. Whether via Ethereum’s builder marketplaces, Solana’s plugin-oriented block scheduler, or Arbitrum’s time-slot auctions, the ecosystem is acknowledging that MEV is here to stay – and the best way to handle it is to formalize it. This sets the stage for comparing these structured MEV markets and the trade-offs they entail.

Toward Structured MEV Markets: Design Trade-offs and Challenges

The introduction of systems like Solana’s BAM and Arbitrum’s Timeboost signals a broader shift towards structured MEV markets, where extraction of MEV is coordinated through formal mechanisms (auctions, marketplaces, plugins) rather than left to implicit competition. This marks a new phase often referred to as “cooperative MEV”, in which various participants (validators, searchers, users, protocol developers) coordinate to share the value from MEV, instead of fighting over it in adversarial ways (flashbots). While promising, this shift comes with complex design trade-offs. I examine a few key considerations:

- Predictability vs Composability: One goal of structured markets is to make transaction ordering and execution more predictable. For instance, with Timeboost a searcher can predict that if they win the auction, they will get priority for the next minute – there’s a guaranteed slot. With BAM, a developer can predict that if they deploy a plugin, transactions affecting their app will follow certain rules. This predictability can improve user experience (fewer surprise reordering events) and allow sophisticated strategies to plan around known rules. However, preserving the open composability of DeFi is a challenge. In a fully permissionless environment, anyone can compose transactions across protocols freely; if each protocol or each block comes with custom scheduling logic, there’s a risk of isolations. For example, imagine a DEX using a BAM plugin that enforces batch auctions every second, while another uses continuous order flow – a complex arbitrage that straddles both might be harder to execute atomically. The designers of these systems must ensure that increased structure doesn’t inadvertently balkanize the trading ecosystem or break atomic composability across applications. So far, it appears BAM and Timeboost are handling this by operating at a fundamental layer (the block level) and keeping the default behavior for those who don’t opt in. In BAM, if you don’t use a plugin, your transactions are just ordered fairly as normal – and plugins can be designed to still allow interleaving with general order flow (they likely would focus only on specific tx patterns). On Arbitrum, if you’re not the express lane controller, your transaction still gets executed, just 0.2s later, which doesn’t break composability in the sense that within each block the relative order of all non-express transactions remains by arrival time. Composability is thus maintained, but there is an additional scheduling layer to account for. Developers and traders will adapt to these new "semantics", perhaps by new standards (e.g. an app might detect if it’s in an express lane interval or if a certain ordering assurance exists). The goal is to get the best of both worlds: predictable execution where needed (for fairness or guaranteed inclusion) while retaining the ability to compose any transactions together. It’s a delicate balance, and careful protocol design and auditing is needed for each new plugin or auction rule to ensure it interacts safely with the broader system.

- Revenue Alignment vs Decentralization Risks: A major argument for structured MEV markets is aligning incentives – redirecting MEV revenue to those who uphold the network (validators, stakers, application builders, or the community via a DAO) rather than letting it all accrue to fast arbitrageurs. This can strengthen the network: e.g., higher validator/staker rewards improve security and decentralization by attracting more participants. Solana’s Jito showed this by boosting validator incomes and even passing some MEV to stakers, aligning MEV extraction with user interests (squads). Arbitrum’s Timeboost similarly would give the DAO (and by extension ARB token holders) a new income source, aligning the chain’s success with MEV capture arbitrumforum. However, introducing new revenue streams and roles can pose centralization risks. For example, if running a BAM Node (scheduler) is very lucrative, will that role concentrate to a few actors? In the initial BAM design, Jito Labs itself is running the only scheduler nodes – a necessary bootstrapping step, but one that explicitly introduces a new centralized component in Solana’s otherwise decentralized validator set. The plan is to open this up over time (50+ independent BAM Nodes in the final phase) (devbam), but it requires vigilance to ensure a diverse set of operators actually materialize. Additionally, TEEs have their own trust model (relying on Intel/AMD security, etc.), and if one party had the majority of BAM Nodes, users would need to trust that hardware and operator. Arbitrum’s auction, on the other hand, could concentrate power in the hands of whoever has the deepest pockets to win slots consistently. If, say, a large trading firm can afford to win 90% of Timeboost intervals, they effectively become a privileged sequencer for those intervals. The Arbitrum team addresses this by noting that continuous competition and cost will prevent one player from permanently monopolizing the express lane (docs.arbitrum) – it would get too expensive to win every round, especially if opportunities are sporadic. Moreover, even a dominant winner only gets a small time edge, not total control over block content (docs.arbitrum) (medium). Nonetheless, the possibility of power imbalances remains. If not carefully monitored, structured MEV markets might create new centralized choke points (e.g., a single popular plugin that everyone uses, controlled by one developer, or a single builder winning most blocks on Ethereum – which has already been observed in MEV-Boost scenarios).

- Fairness and Access: Another design challenge is ensuring these new MEV markets are themselves fair and open. With BAM, one must ensure that access to BAM Nodes is equal – i.e. any user or searcher can submit transactions or bundles to them without discrimination. If, hypothetically, BAM Node operators started making private deals or accepting only certain order flow, it could recreate the “exclusive order flow” problem PBS is trying to solve (flashbots). Jito’s use of TEEs and the public attestation/audit trail is intended to counter this – it makes the scheduling rules transparent and any deviation observable (devbam). Similarly, the Timeboost auction must be accessible: the contract limits each address to a certain number of bids per round to prevent spam, and anyone can participate by locking funds (docs.arbitrum). But smaller players might feel outmatched if they can’t afford to bid what larger players can. One mitigating factor is that Timeboost is optional – if an app or user really needs priority, they could bid for it or collaborate with a searcher who does, but if they don’t, they lose nothing besides 200ms. On Ethereum’s side, proposals like SUAVE emphasize decentralized and permissionless participation – any builder or searcher should be able to join the auction network, and any user can submit transactions into it (flashbots). The challenge will be keeping these systems open as they grow, and preventing the emergence of neo-cartels (e.g. a collusion of top searchers to rotate auction wins, or a handful of node operators setting plugin fee levels). Robust governance (like Jito’s DAO oversight) and transparency (publishing all auction results, open-sourcing code) are tools being used to tackle this.

- Complexity vs Simplicity: One often under-discussed trade-off is that these mechanisms add complexity to blockchain operations. Simplicity has its virtues – a pure FCFS or highest-gas-wins system is blunt but easy to understand. Once we add multi-layer auctions, secure enclaves, and plugin architectures, the system becomes harder to reason about and test. Bugs in these MEV markets could have serious consequences (e.g. a flaw in a BAM plugin could be exploited to reorder transactions incorrectly, or a bug in the Timeboost auction could let someone gain priority without paying).

In weighing these trade-offs, one thing is evident: there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Each blockchain is optimizing for its own use cases and values. Ethereum, prioritizing decentralization and security, is moving a bit cautiously with in-protocol PBS and supporting third-party innovations like MEV-Share (which returns some MEV to users) and SUAVE for cross-domain coordination. Solana, prioritizing high performance and a NASDAQ-like experience, is embracing a sophisticated in-protocol market approach with BAM to attract institutional-level trading activity with fairness guarantees. Arbitrum, as a rollup, is innovating at the sequencer level to balance user experience with protocol revenue. It’s a grand experiment across the industry: can we turn MEV from a dark forest into a sustainable, ecosystem-friendly market? Food for thought kek.

The possibilities BAM unlocks- The decentralized NASDAQ.

Differences Between Timeboost and BAM

| Aspect | Timeboost | BAM (Block Allocation Market) |

|---|---|---|

| Ecosystem | Arbitrum (Layer 2 Ethereum rollup) | Solana |

| Mechanism | Auction where transaction priority is determined by a combination of submission time and bid size | Auction where block space is sold to builders who then determine transaction ordering within their allocated block |

| Auction Timing | Transactions are ranked at the point of inclusion into the sequencer’s mempool | Bids occur for the right to produce an entire block |

| Primary Metric for Priority | Combination of earliest submission time and highest fee bid | Highest bid from block builders determines allocation |

| Role of Fees | Tip size influences priority alongside timing | Builders pay validators for block rights; revenue shared among network participants |

| Integration Level | Implemented natively within Arbitrum's sequencing logic | Separate market layer managed by Jito Labs on top of Solana’s validator infrastructure |

| Primary Objective | Balance fairness and profitability in transaction ordering while mitigating harmful MEV | Formalize MEV extraction and return a portion of MEV revenue to validators |

Similarities Between Timeboost and BAM

| Shared Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Both aim to formalize MEV markets to improve transparency and fairness |

| Auction-based Mechanism | Both use auctions to determine transaction or block priority |

| MEV Formalization | Both move MEV extraction from informal/private channels into structured systems |

| Validator Incentives | Both provide revenue opportunities for validators |

| Mitigation of Harmful MEV | Both designed to limit negative externalities of MEV, like front-running |

Advantages and Drawbacks of Timeboost vs BAM

| Aspect | Timeboost (Arbitrum) | BAM (Solana) |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | - Simple to integrate into existing sequencer logic.- Turns latency wars into a transparent auction, reducing spam.- Preserves private mempool, preventing frontrunning.- Generates DAO revenue from MEV without harming UX (only ~200ms delay).- Compatible with future decentralized sequencer designs. | - Introduces verifiable fairness via Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs).- Enables programmable blockspace through Plugins.- Keeps transactions encrypted until execution, preventing mempool-based MEV.- Shares MEV revenue with validators, stakers, and plugin developers.- Opens design space for advanced market mechanisms (batch auctions, dark pools). |

| Drawbacks | - Limited to transaction-level prioritization (no block-level programmability).- Doesn’t address MEV types outside time-priority advantages (e.g., app-specific MEV).- Auction frequency (every ~1 min) may miss rapid opportunity shifts.- Still relies on a centralized sequencer (for now). | - More complex architecture (additional BAM nodes, validators, plugins).- Initially centralized (small set of validator partners in alpha).- Hardware dependency on TEEs may create trust/availability concerns.- More moving parts mean greater coordination and governance overhead. |

Future Outlook: Structured MEV Markets and the Road Ahead

Both BAM and Timeboost are early exemplars of what could be a sweeping change in how blockchains handle transaction ordering. Looking ahead, we can posit several developments and open questions for these systems and draw comparisons to Ethereum’s trajectory:

- Solana’s BAM – Will it extend to more roles or layers? In its initial design, BAM inserts the scheduler (BAM Node) role between users and validators, and introduces plugin developers as first-class participants in block building. One could ask: will Solana (or Jito) extend this concept further? For example, could we see additional specialization among BAM Nodes (some focusing on certain types of order flow, like an NFT-specialist scheduler)? Or perhaps an order flow market for users – imagine users specifying preferences via plugins (e.g. “I allow my transaction to be delayed up to 500ms if I pay less fee”) which introduces a whole new dimension of blockspace pricing. It’s conceivable that if BAM is successful, Solana might integrate aspects of it even deeper into the protocol or consensus. Already, Solana’s core devs are involved (the Solana Foundation is on the advisory committee for BAM’s rollout (devbam), signaling this is a strategic direction. One area to watch is interaction with Solana’s upcoming Firedancer client (a high-performance validator client by Jump Crypto). Firedancer will drastically increase Solana’s throughput; how will BAM scale alongside it? Potentially, BAM’s programmability could extend to cross-chain or multi-slot coordination in Solana’s future. For now, the focus is on decentralizing the BAM Nodes and proving the plugin model. In a year or two, if dozens of plugins emerge (for fair trading, for specific DeFi protocols, etc.) and a wide set of node operators run the marketplace, Solana could effectively have a permissionless, multi-role MEV economy unlike anything on other chains. The additional roles we might imagine include plugin marketplaces (where different plugins compete or compose with each other) and user-level bidding (users choosing which plugin or node to send to based on desired outcome). Solana will also likely explore connecting BAM to its fee markets – perhaps adjusting transaction fees based on whether they go through BAM or not. In summary, Solana’s path with BAM is one of extensibility: starting with core block building and potentially extending to every actor in the transaction pipeline. If BAM succeeds, it wouldn’t be surprising to see its concepts influence other ecosystems or even become a model for an Ethereum execution shard in the future.

- Arbitrum’s Timeboost – Decentralizing without losing the magic: Arbitrum faces the challenge of shedding its centralized sequencer to align with Ethereum’s ethos, while trying not to lose the benefits that Timeboost provides. If the sequencer becomes a decentralized committee (say 10+ validators rotating or running a BFT consensus), implementing Timeboost means the auction winner’s transactions must somehow get priority in the consensus ordering. This could be done by having the committee collectively agree to always order express lane txs first (perhaps the sequencer leader of each round ensures that). The Offchain team has already thought of this (their spec on Timeboost with decentralized sequencing is in the works (docs.arbitrum). A big question is who gets the revenue in that scenario – presumably, if the DAO enables it, the revenue still goes to the DAO (chain treasury) rather than individual sequencer nodes, to avoid incentivizing them to collude. We might also wonder if Arbitrum could extend Timeboost beyond just one express lane. Could there be multiple priority levels (e.g. first and second place auctions)? For now, they chose a binary express vs normal model for simplicity and to preserve UX. Another future consideration: as Arbitrum explores anytrust or decentralized sequencer models, there’s talk in the community about having multiple sequencers in parallel (for load balancing or redundancy). If that happens, Timeboost might need adjustment (perhaps each sequencer runs its own auction or they share one global auction). The overarching goal for Arbitrum will be to maintain fast and fair ordering as it decentralizes – Timeboost is a tool to ensure fairness (no free MEV for insiders) and to monetize sequencing. It aligns with the broader trend of rollup sovereignty, where rollups seek revenue sources independent of L1. In Arbitrum’s case, Timeboost could make the chain financially self-sustaining (earning fees to pay for sequencing and maybe even share with users).

- Ethereum’s Long-Term Direction – PBS and SUAVE: Ethereum provides an interesting contrast and backdrop. While these L2 and sidechain solutions are forging ahead with their own MEV markets, Ethereum L1 is moving carefully. In parallel, Flashbots’ SUAVE aims to be a network-agnostic MEV platform that could connect to Ethereum and many other domains, offering a unified auction for order flow (flashbots). If SUAVE comes to fruition, a searcher could post a bid for an arbitrage that spans, say, Uniswap on Ethereum and a lending protocol on Arbitrum, and the SUAVE network (with its decentralized builders) might execute on both domains, splitting fees as needed. This is a very ambitious vision and would require significant adoption. How does this compare to BAM and Timeboost? In a way, SUAVE is trying to do what BAM does (privacy and fairness in block building) but across all chains and without requiring each chain to trust a single entity. SUAVE would use techniques like encrypted mempools (maybe even TEEs, as Flashbots has experimented with those too (edennetwork) and economic mechanisms to decentralize block building. Ethereum researchers are also discussing MEV smoothing (to distribute MEV gains over time among validators) and crLists / threshold encryption (to hide transactions in mempool until they’re included) – these are more on the “minimize MEV” side of the spectrum rather than extracting it. By contrast, Solana and Arbitrum’s latest moves are about cooperative extraction. It will be fascinating to watch whether Ethereum leans more into extraction (via PBS auctions, builders, etc.) or into minimization (via encryption, etc.), or both. There is a world in which Ethereum’s PBS + SUAVE + MEV-Share ends up giving users perhaps the best execution (refunds for MEV, etc.), but possibly at the cost of more complexity and maybe ceding some MEV to external systems (SUAVE might take some MEV cross-chain). Solana’s approach is a bit more vertically integrated – keep the MEV and its solutions on-chain via BAM, and use hardware for trust. Arbitrum, as a domain, sits somewhere in between.

- Cross-Pollination and Standardization: Another future development is whether these approaches converge or set standards. Will Solana’s BAM inspire an Ethereum EIP for “plugin transactions” or enshrined block builders? Will Timeboost’s success lead to a standardized “express lane auction” module that any rollup can plugin to their sequencer code? It’s quite likely that good ideas won’t stay confined. If BAM dramatically increases Solana’s DeFi activity by offering trust-minimized fairness (say institutions flock to Solana because they can get CLOB execution with no MEV), Ethereum devs might push similar features (there’s already research into encrypted mempool and fair ordering on Ethereum – e.g. the concept of “FBA” frequent batch auctions in Ethereum consensus (research.arbitrum). Similarly, if Timeboost proves that users don’t mind a tiny delay and the DAO earns millions, other chains will copy it – perhaps even L1s like Avalanche or Polygon PoS could adopt express lane auctions as a protocol upgrade to capture value.

- User Empowerment: Thus far, most structured MEV solutions treat users somewhat passively (they benefit indirectly via lower spam or DAO revenue, but they don’t directly control MEV). In the future, we might see users more directly involved. One concept is user bidding or MEV rebates: for instance, users could specify in a transaction that “if any MEV is extracted around this tx (like it gets sandwiched), redirect the sandwich profit to me or to the protocol treasury.” There are designs like MEV-Share on Ethereum where users share some info about their tx in exchange for a cut of the MEV it generates (flashbots). Structured markets could facilitate this – e.g. a BAM plugin could enforce that any profit made from backrunning a trade gets paid to the user’s address. The more formal the system, the easier it is to enforce such rules. We already see glimmers: Flashbots Protect and Eden Network aimed to give users a say in avoiding MEV; Jito’s stake pool gives users a way to opt into MEV gains. It’s plausible that in a mature MEV market, end-users might choose different “lanes” for their transactions: a fast lane (higher fee, no MEV guarantees), a protected lane (maybe slower or with a fee to ensure no sandwiching), or a pay-me lane (where they auction off the right to backrun their transaction and get paid for it). These ideas could leverage the frameworks of BAM or Timeboost. For example, Arbitrum’s express lane concept could be extended: a user might delegate their transaction to a searcher who bids in the auction, splitting the profit with the user. None of this is far-fetched – it’s basically taking what’s informally happening (searchers paying users via protocols like Rook or via backrunning tokens) and moving it on-chain.

Overall, the trajectory is toward greater formalization and integration of MEV into blockchains’ economic and technical designs. Just as transaction fees became a formal part of protocol design (with models like EIP-1559), MEV auctions and allocations might become a standard component.

Conclusion: Formalizing MEV and the New Phase of Cooperative Extraction

In the span of a few years, MEV discourse has evolved from identifying a problem (“miner/front-runner extracting value at users’ expense”) to engineering sophisticated solutions that turn that problem on its head. We are now entering an era where MEV is neither ignored nor simply fought – instead, it’s formally harnessed and shared. Solana’s BAM and Arbitrum’s Timeboost exemplify this new phase of cooperative extraction, each in their own way transforming MEV from a chaotic free-for-all into a structured market with roles, rules, and revenue-sharing.

With BAM, Solana is effectively formalizing an MEV supply chain: rather than pretend block producers won’t chase MEV, it embraces the idea but under a transparent framework where all participants (validators, node operators, developers, even users via stake pools) can cooperate in extraction and share the rewards. It provides verifiable fairness – a concept more akin to how regulated exchanges work – ensuring that if value is extracted, it’s done by the book and audited (devbam). The introduction of plugins in BAM hints at a future where the distinction between “MEV searcher” and “DeFi protocol developer” blurs – protocols themselves become the searchers, building their value capture or value protection logic into the block-building process. This aligns incentives in a powerful way: an automated market maker, for instance, could ensure it captures arbitrage that arbitrageurs used to, potentially using that to boost its LP rewards or reduce impermanent loss. The value that was once skimmed by external parties can be recirculated to users or builders. In that sense, formal MEV markets democratize the value flow: no longer solely a game of speed and secrecy, but one of strategy and collaboration.

Timeboost, on the other hand, shows how even a minimal tweak in transaction policy can fundamentally reshape value capture. By awarding a 200ms head-start to the highest bidder, Arbitrum shifts the narrative from “MEV is a necessary evil that traders exploit” to “MEV is an income stream for the community, paid by those who exploit it” (arbitrumforum). It’s almost like a tax on MEV that doesn’t deter the activity but ensures it compensates the public. This too is cooperative in its own way: searchers cooperate with the protocol by paying the protocol, instead of burning all that money in a redundant gas war. And users tacitly cooperate by tolerating the slight delays for a healthier network. Timeboost’s significance within a Layer 2 context is especially noteworthy – it suggests that L2s need not be passive extensions of L1 economics; they can innovate and have their own MEV mitigation and capture mechanisms, potentially outpacing L1 in agility. If Arbitrum decentralizes its sequencer while keeping Timeboost, it would be a milestone: a decentralized network running a built-in MEV auction for sequencing rights.

Both BAM and Timeboost, despite differences, highlight a key implication: the value extracted via MEV is being increasingly returned to the ecosystem – whether to validators, DAO treasuries, or users – rather than purely to opportunistic traders. This is a positive development for blockchain sustainability. High MEV used to be seen purely as a problem (it can still destabilize if unchecked), but formalizing it means it can also be a resource. For Ethereum, high MEV in DeFi summer 2020 meant horrendous user experiences; by Ethereum’s next bull cycle, high MEV might mean well-funded public goods (if auctions like PBS/SUAVE route funds to protocol development or users get rebates). For Solana, formal MEV could mean differentiation – attracting projects that demand fairness (like institutional trading platforms) because Solana can offer execution assurances no other chain can yet. For rollups like Arbitrum, it could mean financial independence – less reliance on VC money or token issuance if the chain’s own activity funds its operations via MEV auctions.

Of course, this formalization is not a panacea. It introduces new complexities and trust assumptions, as discussed. There will be an ongoing tension between cooperative extraction and MEV minimization. Interestingly, both BAM and Timeboost focus on minimizing the harmful forms of MEV (e.g. sandwiching is mitigated by BAM’s privacy and by Arbitrum’s private mempool) while formalizing the beneficial/inevitable ones (arbitrage, liquidations) into auctions or plugins (prnewswire) (docs.arbitrum). This indicates a maturing perspective: instead of trying to eliminate all MEV (which may be impossible as long as markets exist), aim to civilize it – channel it in ways that align with user benefit and network health. It’s akin to how real-world markets moved from curb trading and bucket shops to regulated exchanges and dark pools with oversight; we’re witnessing a similar evolution in crypto markets’ microstructure.

In conclusion, MEV is transitioning from a dark art to an open science. The formal markets of BAM and Timeboost are early but concrete steps toward making blockspace a true marketplace – one that can be designed, optimized, and made fair, rather than one that is exploited in the shadows. We see through these examples that when properly engineered, MEV need not be a zero-sum predation on users, but can become an orchestrated value flow that benefits users, builders, and validators alike. Ethereum’s research collective phrases it as moving toward an MEV-positive-sum world, a “new cooperative phase” (flashbots). The cooperative extraction mechanisms pioneered on Solana and Arbitrum are tangible embodiments of that idea. They formalize and legitimize value capture in a way that could ultimately strengthen the trust in and sustainability of blockchain ecosystems. As these systems are battle-tested and refined, we may soon live in a world where MEV auctions and block-building marketplaces are as standard as gas fees and consensus algorithms – a world where Maximal Extractable Value is no longer viewed purely as extraction, but as Maximum Equitable Value, distributed among those who make the ecosystem thrive.

Key References

- Arbitrum Foundation Forum, https://forum.arbitrum.foundation/

- Arbitrum Documentation – Timeboost overview, https://docs.arbitrum.io/how-arbitrum-works/timeboost/gentle-introduction

- BAM (Block Assembly Marketplace official site), https://bam.dev/

Comments ()